An interesting component of education – one that all of us struggle with much of the time – is that part of it is a mental game.

I truly believe that we’re all always ready to learn, given the right circumstances and the right environment; that human beings have the innate desire to learn more about themselves and the world around them, and that part of our job as educators it to create the aforementioned circumstances and environments necessary to facilitate that learning. Most of us have encountered firsthand, however, that our educational system sometimes unintentionally blocks that desire from students by convincing them that they are not capable (or as capable as their peers). Thus, creating the ‘right environment’ for those students to learn is partially about creating the right ‘inner environment’ – changing their mindset, altering the processes of their ‘mental game.’

Thus, when meeting with students and parents during conferences, I find myself often describing metacognitive techniques that students can use to both persevere in and enjoy challenging work rather than talking about the mathematics around which the conference is supposed to be centered. I think having an understanding of the games our own mind plays with us is as much a part of achieving ‘success’ as is discussing study techniques or areas to be improved upon.

Here’s the analogy I like to use: I see math as being like that New Year’s resolution to go on a run 4 days a week. Whenever I make such a resolution, I spend the first week of the year trying to come up with reasons why I shouldn’t go on the run: I had a really busy and tiring day at work, it gets dark too early, or there’s a one-time exception to see friends. But when I really analyze my motives, I find that the reason I don’t want to run is because it’s uncomfortable, challenging, and generally something miserable that I’d rather not do. I also often see it as a monumental task – I have to complete my goal of x miles or y minutes.

The fact of the matter is, though, that when I lace up the sneakers and get out there, it… well, it really is miserable – for a bit. But after ten or fifteen minutes, I start to find my groove; I relax into it and find myself actually gaining energy through expending it. The more often I lace up the sneakers and get out there, the easier it is to make that experience enjoyable – the extreme example being people who actually become addicted to running!

Math can be much the same – something that is easy to avoid at all costs, but that once you sit down and practice, can also become an enjoyable puzzle with which to engage. The more often you practice making the experience enjoyable, the more often it begins to happen. And, like a run, it doesn’t have to be a monumental task once a week – it can be a smaller task many times a week.

The nuance to this statement is that with math, it’s not always evident when you are making progress. So, I tell my students about my friend, Brendan, who is a writer. For years Brendan created content and wrote articles, hoping to make a living writing full-time and never quite getting there. He even started collecting hundreds of rejection letters from magazines to which he had sent articles! But Brendan was committed to his dream. This year, he published his seventh book.

Brendan’s story is, of course, one of great success; however, I think it could be easy to tell as a surface-level anecdote that isn’t useful to students (or ourselves – “because we all have dreams, but they don’t mean much if we don’t act on them” -Brendan). The truth of the matter is that Brendan’s story is littered with a lot of really tough moments when he thought it just might be easier to find a different profession, and with a lot of commitment to something known as ‘The Grind.’

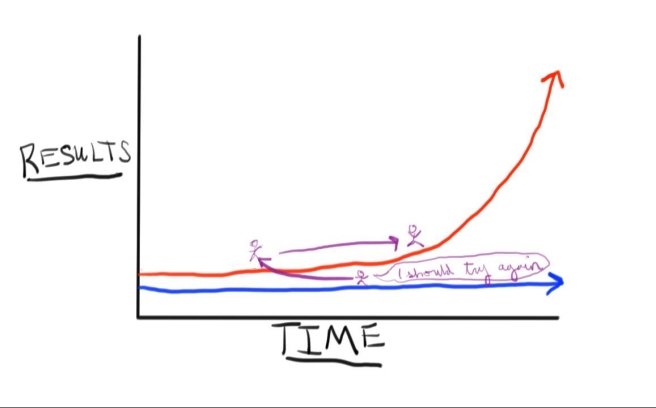

‘The Grind’ is that moment when you have committed to your New Year’s resolution runs, or your nightly math problems, or your writing career, and for what seems like the first time in your life, you are putting all of your efforts and energy into the pursuit, and it still feels like you’re not getting anywhere with it. The reason for this phenomenon is visualized in the highly scientific graph above, drawn to emulate Brendan’s own rendering.

As human beings, whether students or mathematicians or writers, we have a tendency to get discouraged when we are putting what feels like 110% effort into something and not getting any results. At this point, it’s easy to abandon our efforts – to spend our time (but perhaps not necessarily our energy) doing something else. When this happens, we jump from the red, ‘If You Try’ track shown above, to the blue track. Eventually, we realize that we either have to or really should get back on the ‘trying’ bus, and we climb back onto the red track, albeit with effort and further back than the location that we jumped off of it.

This causes our growth (as differentiated from results) to follow a strange looking pattern:

It’s important for us to remember that if we are trying really hard and not getting the results that we feel we should be getting, it’s possible that we need to change our strategy for productivity… but it’s potentially even more likely that we need to recognize that we are on an exponential curve, and that upward curve is just around the bend.

Of course, the Growth curve gives us a different reminder as educators that the graph makes obvious: growth is not a linear process. It’s messy, and our students will grow one week and regress another.

But if we (and they) ‘Pledge Allegiance to the Grind,’ we’ll find ourselves in a position to do something about those big dreams we have.

References:

Leonard, B. (2013). A Bunch of Dreams, One Film: The Making of ’35’. Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://semi-rad.com/2013/04/a-bunch-of-dreams-one-film-the-making-of-35/ (watch the film!)

Leonard, B. (2017). I Pledge Allegiance to the Grind. Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://semi-rad.com/2017/02/pledge-allegiance-grind/